The Sound Revolution of The Blue Angel

In 1930, the first German "talking" film, Der Blaue Engel or The Blue Angel directed by Josef Von Sternberg, was released. The importance of the film, in my opinion, lies not only in its use of sound in a “technically”, but also as a "narrative element”. In a very short time, the film took advantage of the newly developed sound techniques of the time in a way that was very far ahead of its time compared to contemporary films. For me, it represents an important historical moment in the use of sound and a starting point for many important films, such as Fritz Lang's M.

In 1930, the first German "talking" film, Der Blaue Engel or The Blue Angel directed by Josef Von Sternberg, was released. The importance of the film, in my opinion, lies not only in its use of sound in a “technically”, but also as a "narrative element”. In a very short time, the film took advantage of the newly developed sound techniques of the time in a way that was very far ahead of its time compared to contemporary films. For me, it represents an important historical moment in the use of sound and a starting point for many important films, such as Fritz Lang's M.

In 1927, Specifically in America, a film called The Jazz Singer was released, which was the first "talking" film in the history of cinema. Due to the fascination of the audience and the success of the film, the introduction of sound into the film industry was accelerated.

Sound recording technology and equipment evolved, and directors began to use them in their films. However, the situation was a bit confusing. In any scene with movement, the films were treated as silent films, and the dialogue scenes were recorded with sound, nothing more and nothing less.

This was what fascinated me about The Blue Angel, how much it was ahead of its time in treating sound and using it as a narrative and expressive tool.

The soundtrack of this film is full of details that are much more complex than the dialogue. For example, there is a very strong focus on the sound of the space—which was almost non-existent before this film. The sounds of each place are built in a very conscious way, the streets at different times of the day with different levels of congestion, the laughter and shouting of people in the cabaret, the distant sound of music coming from outside in the middle of the dialogue, small details like these are what create a unique world for the film.

One of the greatest things that sound has brought to cinema, in my opinion, is "silence", and its use in the film was very intelligent and ahead of its time. There were cuts from very loud moments to completely silent moments to create tension, and intense emotions.

The Blue Angel stands out not just for being an early "talkie," but for its groundbreaking use of sound as a storytelling tool. By meticulously crafting soundscapes and employing strategic silence, the film creates a truly immersive experience far exceeding the limitations of its contemporaries. This innovative approach to sound design paved the way for future films to explore the full potential of this new cinematic element, solidifying The Blue Angel as a landmark achievement in film history.

UNSPOKEN CONVERSATION

Cinema possesses a captivating ability to capture human emotions and relationships. Equally fascinating is how the personal experiences of its creators help us discover insights about ourselves.

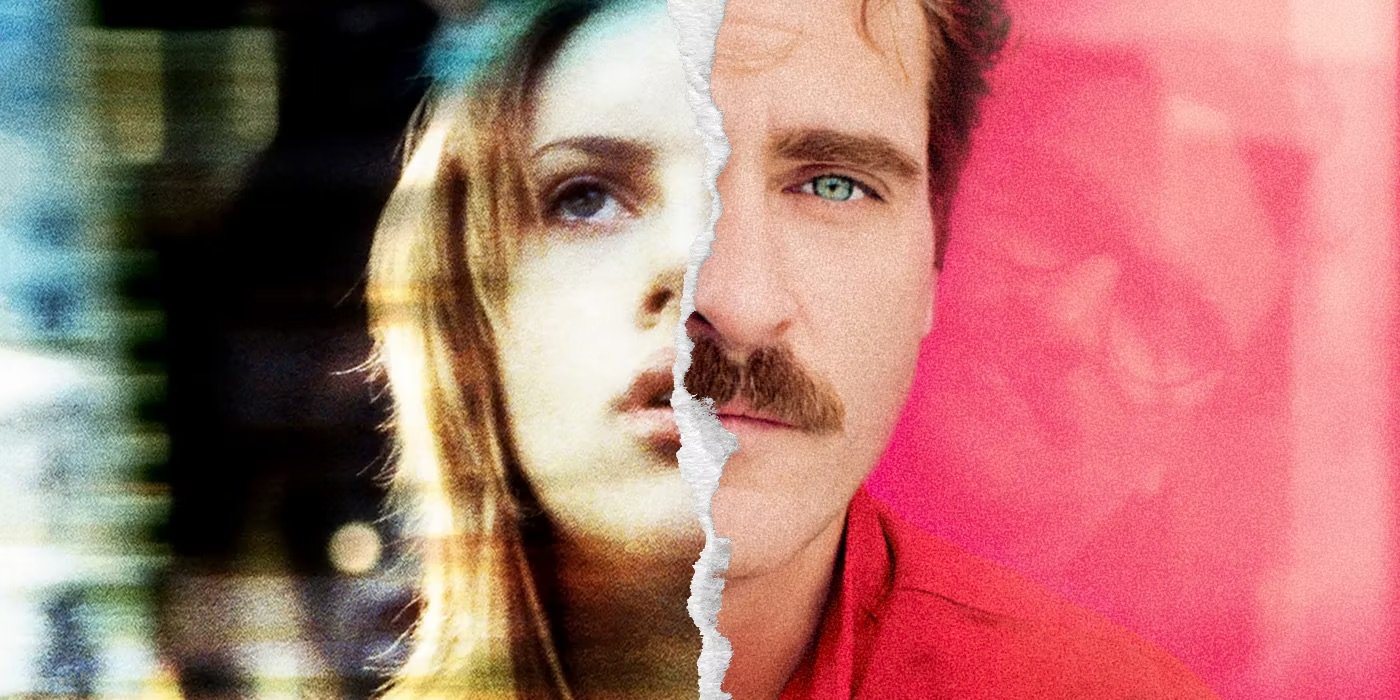

There’s one case that deeply connects with me, and it involves two films I truly adore: Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation and Spike Jonze’s Her.

Cinema possesses a captivating ability to capture human emotions and relationships. Equally fascinating is how the personal experiences of its creators help us discover insights about ourselves.

There’s one case that deeply connects with me, and it involves two films I truly adore: Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation and Spike Jonze’s Her.

Apart from the fact that Coppola and Jonze are among the most talented directors of their generation, they were once married. Both films were created after their divorce, and due to the content of these films and several other factors I’ll discuss, we can argue that both films tell a similar story.

In 1999, Sofia Coppola and Spike Jonze tied the knot. At that time, both were enjoying successful points in their careers. Sofia had just garnered critical acclaim for her debut film, The Virgin Suicides, while Spike, known for his groundbreaking work in the music video industry, made his directorial debut with Being John Malkovich, establishing himself as a visionary filmmaker. Unfortunately, in 2003, they ended their marriage with a divorce.

Sofia Coppola and Spike Jonze are both, in one way or another, artists who craft “personal projects.” Their lives and experiences play a significant role in shaping their narratives and their art.

In this context, one can analyze both films in tandem, uncovering their shared elements as well as their differences, which reflect the marriage and divorce experiences of each filmmaker. What’s particularly intriguing is how each of them perceives themselves and the other person within their respective stories.

Lost In Translation

Sofia’s film narrates the tale of two individuals adrift in their lives. Charlotte is an emotionally neglected wife, married to John, a photographer who is always immersed in his work. Their relationship lacks any genuine connection, leaving her mostly alone in Tokyo, where he is busy with his job. Bob, on the other hand, is a middle-aged actor who has lost his fame and glamour. His family relationships are strained, and he arrives in Tokyo to shoot a commercial for a whiskey company, feeling lost and as if he’s merely going through the motions of life.

At its core, Lost In Translation is a film that explores themes of loneliness, isolation, the loss of connections, and the search for meaning.

Throughout the story, Charlotte grapples with a profound sense of isolation. Even when her husband is physically present, he remains emotionally distant. In Tokyo, she finds herself alienated from the culture and language, struggling to establish any meaningful connections, even with her own self.

The initial time we encounter Charlotte in a full view on screen is in a long shot, where she sits before a large hotel window, enveloped by the sprawling cityscape before her, a visual portrayal of her isolation.

Charlotte subsequently endeavors to establish a connection with her surroundings and embarks on a quest for purpose. She engages in cultural activities, explores the city on foot, and goes as far as purchasing an audiobook on the pursuit of meaning. Ironically, each attempt she makes only serves to distance her further, intensifying her feelings of alienation and isolation rather than leading her toward a connection.

After some time, Charlotte undergoes an existential crisis that deepens her disconnect from both herself and her life, leaving her at a crossroads where she begins to question the choices she has made.

Charlotte’s primary issue lies in the emotional disconnect between her and John. The aimless moments they share, coupled with their shallow interactions with his friends, illuminate the vast chasm and emptiness within their relationship. This prompts her to seek connection elsewhere.

This occurs when she meets Bob. From the moment they meet, a distinctive and profound connection blossoms between them. Both of them are adrift and experiencing difficult phases in their lives, both emotionally and psychologically. Their conversations create a sense of companionship, reassuring them that they are not alone, and they swiftly forge a significant understanding and connection.

The lost Bob unexpectedly assumes the role of a mentor figure for her, offering life guidance that in many ways reflects his own inner dialogue. Meanwhile, Charlotte rekindles Bob’s zest for life, culminating in a captivating sequence where they playfully run through the neon-lit streets and arcade spaces of Tokyo, evoking a childlike sense of joy.

Throughout the journey of Bob and Charlotte, Lost In Translation profoundly delves into themes of isolation, disconnection, and the search for meaningful connection.

Her

Her takes place in a futuristic city and narrates the tale of Theodore, a recently divorced and isolated man who develops a romantic relationship with Samantha, an artificial intelligence — ironically played by Scarlette Johansson.

Her explores themes of loneliness, isolation, and the search for a profound connection. It also raises inquiries about the nature of such connections and the challenges of moving forward after losing a deep and meaningful relationship, in a really thought-provoking premise.

Following his divorce, Theodore became an extremely isolated individual. Catherine’s departure leaves him in a state of grief and emptiness that he struggles to cope with, creating a complex situation that the film goes on to explore.

His coping mechanism involved immersing himself in the new games and technologies of the era, ultimately leading to his encounter with the AI, Samantha.

In Samantha, he finds the companionship he had been missing. She provides him with a sense of intimacy that he had struggled to find in other people following Catherine’s departure. Samantha essentially becomes his sanctuary, effectively filling the void left by Catherine.

In this context, the film unveils the complexities and contradictions inherent in the solution Theodore has found. Even though Samantha fulfills his needs, it raises questions about the authenticity and sincerity of their relationship.

Two Films, Two Directors, One Conversation

The distinctions and resemblances between the two films mirror Sofia and Spike’s perspectives on their marriage and divorce.

Essentially, both films revolve around coping with isolation following the conclusion of a significant relationship.

In Lost In Translation, Charlotte grapples with the aftermath of her “emotional breakup” with John, which leaves her deeply isolated within her own world and self.

In Her, Theodore severs his connections with both the world and himself following his divorce from Catherine, resulting also in his own isolation.

This serves as the starting point for both films, and they both delve into the process of grappling with the aftermath of such situations.

Following this period of isolation, both films embark on a search for connection and the pursuit of genuine, meaningful relationships. In “Lost In Translation,” this journey is embodied in Charlotte’s relationship with Bob, while in “Her,” it is epitomized by the connection between Theodore and Samantha.

The conclusions of both films, in a way, convey a sense of hopefulness, but it’s intriguing to note that they are markedly distinct from each other.

Sofia Coppola’s conclusion suggests that in the most distant and unlikely of circumstances, individuals in very distinct phases of life can forge a genuine connection — a rather idealistic conclusion.

On the other hand, Spike Jonze approaches the conclusion with a mature and pragmatic perspective. After his heartbreak, his divorce, and his failed relationship with Samantha, he arrives at the realization that his happiness and sense of connection are not fundamentally dependent on external factors; they must originate from within himself.

As previously mentioned, an intriguing aspect of this analysis lies in the perspectives we hold of ourselves and others, as well as how we are perceived by others on different sides of these parallel narratives.

In the context of both films being narratives about pivotal moments in the lives of their respective filmmakers, we can draw a parallel where Catherine represents Sofia Coppola, Theodore embodies Spike Jonze in Her, and in Lost In Translation, Charlotte represents Sofia while John embodies Spike.

In Sofia’s perspective within the narrative, Jonze’s presence is scarcely evident. He is depicted as an inattentive husband, neglecting her, and lacking any meaningful connection. He remains preoccupied with work and friends, keeping a considerable distance.

In Jonze’s narrative, we witness a different side of him — a kind and sensitive individual who struggles to move on from the divorce. He finds it difficult even to sign the paperwork, portraying a John, or Jonze, in contrast to what we saw in Sofia’s perspective.

Similarly, this duality applies to Charlotte and Catherine. Charlotte is depicted as a successful but lost individual in need of support, love, and meaningful connection from her partner. However, in the case of Catherine, Jonze adopts a more conservative approach, showing her only through fleeting glimpses of happy memories, reflecting what he remembers or perhaps what he chooses to remember.

The realization of how we perceive ourselves and others, and how we are perceived, is a fascinating and thought-provoking subject. Despite having shared years together, when each one speaks about the other and themselves, we observe two entirely distinct individuals.

Personally, I hold an appreciation for both films, with perhaps a slightly stronger affinity for Lost In Translation. Moreover, I value them even more when viewing them as an unspoken dialogue between Sofia and Spike.

Le Temps Detruit Tout

Like many of Gaspar Noé's films, Irreversible is controversial and horrific in its depiction of sexual and physical violence, which has made it hard to see (or, as some have put it, unwatchable).

A large number of spectators left the Cannes Film Festival in 2002 during the film’s screening. People said it "wasn't a film", and if that's the case, then why is it showing at the festival? At first look, one could even come to agree with this...but Irreversible is a "film" and a significant one that offers an interesting philosophical and intellectual argument.

The phrase "Le Temps Detruit Tout" is spoken by a character who had previously appeared in two Noé films prior to Irreversible. However, we will not be discussing this character here; instead, we will return to the statement. Considering this sentence and its meaning, the sentence translates to, "Time destroys everything." Taking this sentence into consideration along with In the narrative form of the film, it is possible to take the film seriously intellectually and philosophically.

The presence and clarity of cause and effect is an important element of the conventional film structure. It is the idea that everything that takes place has a purpose and ultimately leads to the next event. The film Irreversible does a good job of maintaining this, but it goes even further than that. It turns it around.

The plot of the film irreversible is told in reverse. As we'll see, the very first scene of the film serves as the story's climax.

As with the subsequent Noé films, the film opens on a street where the camera floats . It then takes us into a room where two men are chatting. And it is at this very moment when the words "Time destroys everything" are said. They talk about their perspectives on what constitutes good and evil, arguing that there are no deeds that are fundamentally good or wicked; rather, there are only actions.

The next action unfolds on a street outside a building called "Rectum." A man who is unconscious is carried out onto a stretcher and subjected to insults from the onlookers. Subsequently, another man comes out from the building, and the police detain him.

We learn that the "Rectum" is a BDSM Gay Club and that the two are on the hunt for a guy named "La Tenia" in the subsequent scene, where we see them entering the building together. His friend Pierre, who had been arrested, came to his rescue and brutally killed the man with a fire extinguisher after Marcus, who had been on a stretcher in the previous scene, clashed with someone who they suspected of being La Tenia. The man broke Marcus's arm and attempted to rape him.

In the following scene, Pierre and Marcus are in a cab, and they want to know the address of a place called "Rectum." Everyone who has watched the film up to this point should be able to understand how the movie works.

They are joined by a gang of young men in the street as they search for an individual identified as "Guillermo Nunez" in the following scene. After some time, we learn that the individual is actually a transgender prostitute named Concha, and they start questioning her to find out where "La Tenia" is. Following considerable physical force and threat, she finally reveals that he is in a location known as "Rectum."

The following scene finds Pierre and Marcus in shock and breakdown, standing in front of police and paramedics. Marcus is asked by the young man from the previous scene if he wants retribution, and the answer is yes.

After then, we see Marcus and Pierre standing outside what appears to be a house after a party. A woman on a stretcher emerges from a tunnel, and they witness her. As soon as Marcus lays eyes on her, he recognises his girlfriend Alex and learns that she was raped in the tunnel.

After Alex exits the party, the following scene finds her flagging down a cab. A passerby informs her, "The tunnel is better," as she makes her way across the street. In order to cross the street, she heads to the tunnel. She is terrified of the red tunnel, but she is also fearful of someone striking someone. As we move closer, we see that Concha was the one questioning her. At first, she is accompanied by La Tenia. Upon seeing Alex, he immediately leaves her and proceeds to beat, abuse, and rape her in an extremely tough scene that lasts approximately eleven minutes. Here we find out that the man who died wasn't La Tenia; in fact, he was the one who saw them fight in the opening of the film.

Alex, Pierre, and Marcus are shown during the celebration in the subsequent scene. Alex decides to leave the party and walk alone after Marcus treats her outrageously while under the influence of drugs and alcohol.

In the subsequent scene, we observe the trio boarding the metro to reach the celebration, during which we find out that Pierre was once in a relationship with Alex.

In the following scene, we observe Marcus and Alex enjoying a romantic morning together. Alex shares a dream in which she was in a red tunnel. At the end of the scene we know that she is pregnant.

The film concludes with kids playing, and this is where the line, "Time destroys everything," appears again. The film ends with Alex reading a book about dreams in a garden next to the house. This scene also happens to be the first event in the story.

From this point on, we can ask as why the film is structured this way, or perhaps more precisely, as to what would have occurred if it had been presented in a chronologically.

If "Irreversible" had followed a more conventional plot, it may have been another violent Rape & Revenge movie or one dealing with the aftermath of a horrific act. Nevertheless, This is only the beginning of Noé's pessimistic perspective on life and human beings.

Noé is well-known for his films that are considered to be part of "The New French Extremity," which is a movement that prioritises addressing the ugly qualities of mankind rather than blaming or repairing them.

"Time destroys everything" is Noé's attempt to express his pessimistic outlook on life through this film.

We mature, get sick, and go through tough times because of the passage of time. The film Noé elevates the viewpoint through its narrative structure. After witnessing this tragic day, "on the contrary," we do not react positively to the film's third act, which is filled with joy and love. Characters are shown to us, and we are aware of their fates. Still, it remains unknown to them... Time, according to this argument, annihilates not only the future but also our perceptions of the past. Time destroys everything.